Nwadiuto Azugo holds both a BSc in Zoology and an MSc in Parasitology, and is currently enrolled in a PhD programme in Environmental Parasitology and Public Health at the University of Port Harcourt. What drives her is less the prestige of academic titles and more the influence of her father, a former science teacher, retired civil servant and a Doctor of parasitology, and the afternoons she spent at “Auntie Nurse’s” chemist shop, watching community members talk about disease as if it were water in their local tongue.

What would you tell our readers about yourself, your background, and what inspired you to walk this path?

Nwadiuto: My name is Nwadiuto Azugo, I’m from Anambra state. I hold a Bsc in Zoology from Nnamdi Azikwe University, and an Msc in Parasitology. I’m currently a Environmental Parasitology and Public Health PhD candidate in the university of Port Harcourt.

My academic journey, career path and the work I do is inspired by my father, who is a science school teacher in a secondary school in my community. He has a PhD in parasitology. He taught me how to pronounce words like schistosomiasis, taught me about the body mass index.

Also, growing up, there was a community nurse who we called auntie nurse, who had a pharmacy where I would wait for the school bus and watch her explain things to people in their local language while I waited.

What’s the backstory about the earlier days of this work?

Nwadiuto: I’d say it all started with my father, and from watching auntie Nurse. I would sit in front of her chemist shop and watch her communicate with the community members about diseases that I would later learn were neglected tropical diseases.

At the time, as an 8 year-old, I didn’t know they were neglected tropical diseases, but she explained them in very simple ways using their language, idioms, and context that they understood.

Later, during my BSc, I worked with a supervisor who was interested in neglected tropical diseases, starting with soil-transmitted helminthiasis.

We visited local communities and saw firsthand the impact of these diseases on underserved, rural communities.

After graduation, I worked on a WHO project focusing on schistosomiasis, specifically female genital schistosomiasis.

That experience, especially seeing the impact on adolescent girls, changed everything for me and solidified my decision to pursue this field.

Can you explain what female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) is, and why it’s such a serious yet overlooked disease?

Nwadiuto: Before discussing FGS, we have to understand schistosomiasis in general. It’s a neglected tropical disease, meaning it primarily affects poor, underserved communities. It’s caused by parasites of the genus Schistosoma, including S. mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. haematobium in Nigeria.

It’s transmitted through contact with freshwater bodies infested with the parasite, which comes from infected snails. The parasite can penetrate human skin and affect various organs. Schistosomiasis can be intestinal or urogenital, with the latter affecting the urinary and genital tracts.

FGS specifically affects the female genital organs, mainly the cervix. The parasite eggs have sharp terminal spines that create wounds, granulomas, and rubbery patches. These lesions can lead to higher susceptibility to STIs, cervical cancer, infertility, and ectopic pregnancies. Unfortunately, FGS is neglected, even among health professionals.

In 2021, we profiled health workers, from medical students to doctors, workers of different cadres, in Anambra State and found that while they knew about schistosomiasis in general, they were largely unaware of the specifics, like FGS.

This lack of knowledge means women may be misdiagnosed or not receive proper care.

Is there a specific case that impacted you?

Nwadiuto: In Nsugbe, Anambra State, a 12-year-old girl who was not sexually active already had her genital regions severely affected by lesions.

We identified this without even needing colposcopic examination. She eventually received treatment, but it was heartbreaking. FGS is classified as a disease of the poor, but it’s really about access, exposure, and neglect.

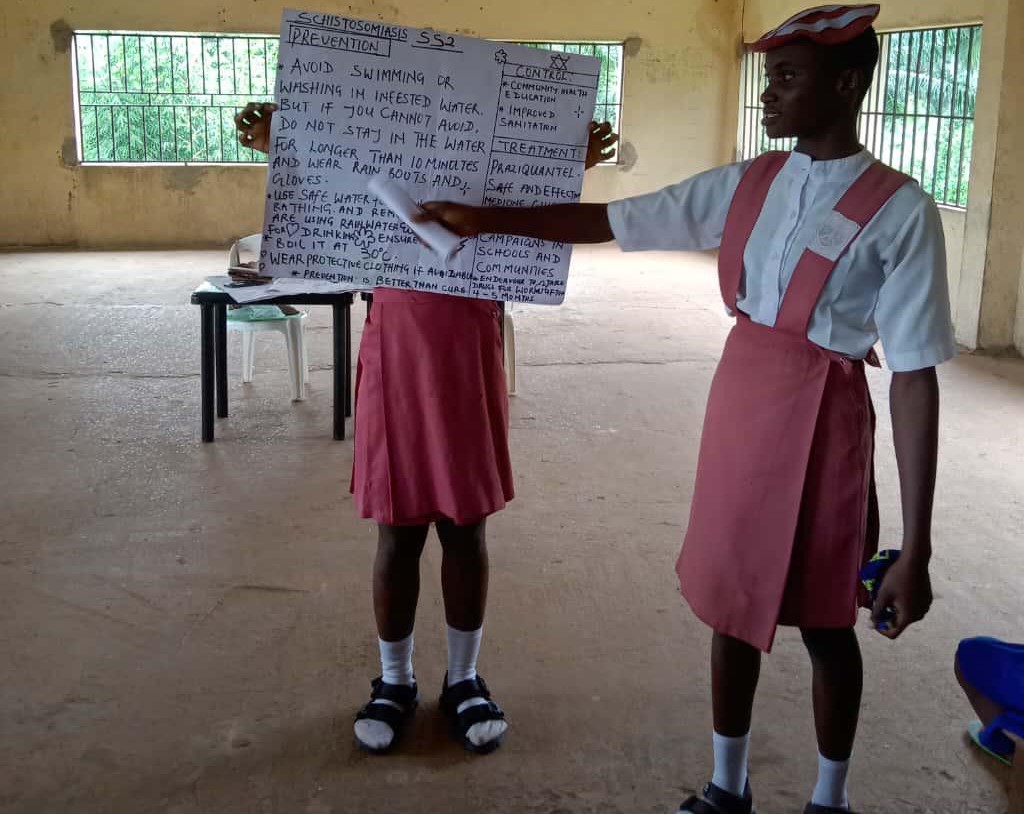

You created the first schistosomiasis Health Club in Anambra, and also write through your blog, Ndu Bu Isi. How has that been going, and what challenges have you faced?

Nwadiuto: The challenges I faced in the field inspired the creation of the health club. Communities often don’t trust health workers or interventions, sometimes due to past negative experiences with researchers who didn’t provide follow-up care.

I realized education was crucial in bridging gaps between health workers and community members. Co-creating with communities, understanding their beliefs, and involving them in interventions became central to our approach.

I also engaged in fellowships like Social Innovation in Health Initiatives, WHO TDR classes, and Women in Global Health Nigeria. These helped me learn about advocacy, policy translation, and community-centered interventions.

Through my blog, I share personal experiences and field observations to educate others outside the academic confines. My father’s advice is to always “tell their story”, the women and girls whose lives are affected by these diseases, their struggles, and their cultural realities.

Working in women’s health can be mentally taxing. How do you take care of yourself while doing this work?

Nwadiuto: I’m grateful for Korean dramas, books, and good friends. When a project ends, there’s often an emotional letdown. My friends encourage me to allow myself to feel those emotions fully, then gradually pick myself back up.

I’m also supported by a network of passionate young women in global health and male mentors who care about women’s access to healthcare. This support system allows me to process emotions, seek advice, and continue my work sustainably.

Finally, is there one misconception about FGS or neglected tropical diseases that you wish to correct?

Nwadiuto: Many people think FGS is a disease of the poor. I do not like that definition. Neglected tropical diseases affect humanity, anyone, regardless of economic status. While they disproportionately affect the poor, they are not exclusive to them.

FGS can impact anyone exposed to freshwater bodies, as seen in a case of a privileged tourist in Tanzania who contracted FGS. Calling it a “disease of the poor” perpetuates neglect and underestimates its global impact.

We need to talk more about these diseases, provide better access to healthcare, and break the misconception that they only affect the poor.

TEYS: Thank you so much, Nwadiuto, for sharing your story and insights. Your work is truly inspiring

Nwadiuto: Thank you too, for having me and for sharing my story.

To connect with Nwadiuto and learn more about the amazing work she does or be a part of her journey, you can reach her on LinkendIn

Do you have a story like this? We’d love to hear it. Fill out this quick form, let’s share your journey with the world. We can’t wait to celebrate you!

I learnt a whole lot. As a public health advocate myself, I’m glad to learn about FGS.

Honestly, I’m glad you do. I learned quite a lot myself.